tl;dr: Don t just

apt install rustc cargo. Either do that and make sure to use only Rust libraries from your distro (with the tiresome config runes below); or, just use

rustup.

Don t do the obvious thing; it s never what you want

Debian ships a Rust compiler, and a large number of Rust libraries.

But if you just do things the obvious default way, with

apt install rustc cargo, you will end up using Debian s

compiler but

upstream libraries, directly and uncurated from crates.io.

This is not what you want. There are about two reasonable things to do, depending on your preferences.

Q. Download and run whatever code from the internet?

The key question is this:

Are you comfortable downloading code, directly from hundreds of upstream Rust package maintainers, and running it ?

That s what

cargo does. It s one of the main things it s

for. Debian s

cargo behaves, in this respect, just like upstream s. Let me say that again:

Debian s cargo promiscuously downloads code from crates.io just like upstream cargo.

So if you use Debian s cargo in the most obvious way, you are

still downloading and running all those random libraries. The only thing you re

avoiding downloading is the Rust compiler itself, which is precisely the part that is most carefully maintained, and of least concern.

Debian s cargo can even download from crates.io when you re building official Debian source packages written in Rust: if you run

dpkg-buildpackage, the downloading is suppressed; but a plain

cargo build will try to obtain and use dependencies from the upstream ecosystem. ( Happily , if you do this, it s quite likely to bail out early due to version mismatches, before actually downloading anything.)

Option 1: WTF, no I don t want curl bash

OK, but then you must limit yourself to libraries available

within Debian. Each Debian release provides a curated set. It may or may not be sufficient for your needs. Many capable programs can be written using the packages in Debian.

But any

upstream Rust project that you encounter is likely to be a pain to get working, unless their maintainers specifically intend to support this. (This is fairly rare, and the Rust tooling doesn t make it easy.)

To go with this plan,

apt install rustc cargo and put this in your configuration, in

$HOME/.cargo/config.toml:

[source.debian-packages]

directory = "/usr/share/cargo/registry"

[source.crates-io]

replace-with = "debian-packages"

This causes cargo to look in

/usr/share for dependencies, rather than downloading them from crates.io. You must then install the

librust-FOO-dev packages for each of your dependencies, with

apt.

This will allow you to write your own program in Rust, and build it using

cargo build.

Option 2: Biting the curl bash bullet

If you want to build software that isn t specifically targeted at Debian s Rust you will probably

need to use packages from crates.io,

not from Debian.

If you re doing to do that, there is little point not using

rustup to get the latest compiler. rustup s install rune is alarming, but cargo will be doing exactly the same kind of thing, only worse (because it trusts many more people) and more hidden.

So in this case:

do run the

curl bash install rune.

Hopefully the Rust project you are trying to build have shipped a

Cargo.lock; that contains hashes of all the dependencies that

they last used and tested. If you run

cargo build --locked, cargo will

only use those versions, which are hopefully OK.

And you can run

cargo audit to see if there are any reported vulnerabilities or problems. But you ll have to bootstrap this with

cargo install --locked cargo-audit; cargo-audit is from the

RUSTSEC folks who do care about these kind of things, so hopefully running their code (and their dependencies) is fine. Note the

--locked which is needed because

cargo s default behaviour is wrong.

Privilege separation

This approach is rather alarming. For my personal use, I wrote a privsep tool which allows me to run all this upstream Rust code as a separate user.

That tool is

nailing-cargo. It s not particularly well productised, or tested, but it does work for at least one person besides me. You may wish to try it out, or consider alternative arrangements.

Bug reports and patches welcome.

OMG what a mess

Indeed. There are large number of technical and social factors at play.

cargo itself is deeply troubling, both in principle, and in detail. I often find myself severely disappointed with its maintainers decisions. In mitigation, much of the wider Rust upstream community

does takes this kind of thing very seriously, and often makes good choices.

RUSTSEC is one of the results.

Debian s technical arrangements for Rust packaging are quite dysfunctional, too: IMO the scheme is based on fundamentally wrong design principles. But, the Debian Rust packaging team is dynamic, constantly working the update treadmills; and the team is generally welcoming and helpful.

Sadly last time I explored the possibility, the Debian Rust Team didn t have the appetite for more fundamental changes to the

workflow (including, for example,

changes to dependency version handling). Significant improvements to upstream cargo s approach seem unlikely, too; we can only hope that eventually someone might manage to supplant it.

edited 2024-03-21 21:49 to add a cut tag

comments

Years ago, at what I think I remember was DebConf 15, I hacked for a while

on debhelper to

Years ago, at what I think I remember was DebConf 15, I hacked for a while

on debhelper to

I work from home these days, and my nearest office is over 100 miles away, 3 hours door to door if I travel by train (and, to be honest, probably not a lot faster given rush hour traffic if I drive). So I m reliant on a functional internet connection in order to be able to work. I m lucky to have access to

I work from home these days, and my nearest office is over 100 miles away, 3 hours door to door if I travel by train (and, to be honest, probably not a lot faster given rush hour traffic if I drive). So I m reliant on a functional internet connection in order to be able to work. I m lucky to have access to

Those of you who haven t been in IT for far, far too long might not know that next month will be the 16th(!) anniversary of the

Those of you who haven t been in IT for far, far too long might not know that next month will be the 16th(!) anniversary of the

They're called The Usual Suspects for a reason, but sometimes, it really is Keyser S ze

They're called The Usual Suspects for a reason, but sometimes, it really is Keyser S ze

The Debian Project Developers will shortly vote for a new Debian Project Leader

known as the DPL.

The DPL is the official representative of representative of The Debian Project tasked with managing the overall project, its vision, direction, and finances.

The DPL is also responsible for the selection of Delegates, defining areas of

responsibility within the project, the coordination of Developers, and making

decisions required for the project.

Our outgoing and present DPL Jonathan Carter served 4 terms, from 2020

through 2024. Jonathan shared his last

The Debian Project Developers will shortly vote for a new Debian Project Leader

known as the DPL.

The DPL is the official representative of representative of The Debian Project tasked with managing the overall project, its vision, direction, and finances.

The DPL is also responsible for the selection of Delegates, defining areas of

responsibility within the project, the coordination of Developers, and making

decisions required for the project.

Our outgoing and present DPL Jonathan Carter served 4 terms, from 2020

through 2024. Jonathan shared his last  A short status update of what happened on my side last month. I spent

quiet a bit of time reviewing new, code (thanks!) as well as

maintenance to keep things going but we also have some improvements:

Phosh

A short status update of what happened on my side last month. I spent

quiet a bit of time reviewing new, code (thanks!) as well as

maintenance to keep things going but we also have some improvements:

Phosh

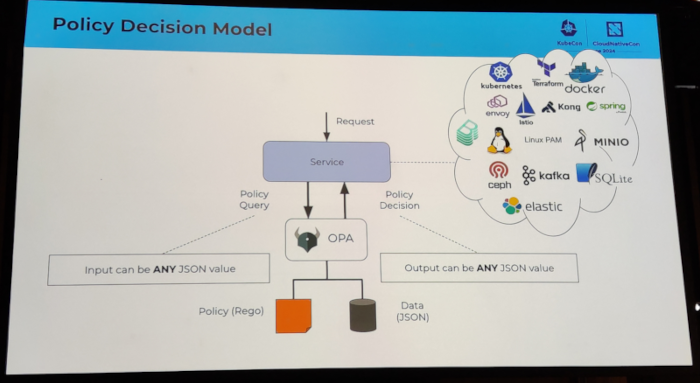

This blog post shares my thoughts on attending Kubecon and CloudNativeCon 2024 Europe in Paris. It was my third time at

this conference, and it felt bigger than last year s in Amsterdam. Apparently it had an impact on public transport. I

missed part of the opening keynote because of the extremely busy rush hour tram in Paris.

On Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and GPUs

Talks about AI, ML, and GPUs were everywhere this year. While it wasn t my main interest, I did learn about GPU resource

sharing and power usage on Kubernetes. There were also ideas about offering Models-as-a-Service, which could be cool for

Wikimedia Toolforge in the future.

See also:

This blog post shares my thoughts on attending Kubecon and CloudNativeCon 2024 Europe in Paris. It was my third time at

this conference, and it felt bigger than last year s in Amsterdam. Apparently it had an impact on public transport. I

missed part of the opening keynote because of the extremely busy rush hour tram in Paris.

On Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and GPUs

Talks about AI, ML, and GPUs were everywhere this year. While it wasn t my main interest, I did learn about GPU resource

sharing and power usage on Kubernetes. There were also ideas about offering Models-as-a-Service, which could be cool for

Wikimedia Toolforge in the future.

See also:

I attended several sessions related to authentication topics. I discovered the keycloak software, which looks very

promising. I also attended an Oauth2 session which I had a hard time following, because I clearly missed some additional

knowledge about how Oauth2 works internally.

I also attended a couple of sessions that ended up being a vendor sales talk.

See also:

I attended several sessions related to authentication topics. I discovered the keycloak software, which looks very

promising. I also attended an Oauth2 session which I had a hard time following, because I clearly missed some additional

knowledge about how Oauth2 works internally.

I also attended a couple of sessions that ended up being a vendor sales talk.

See also:

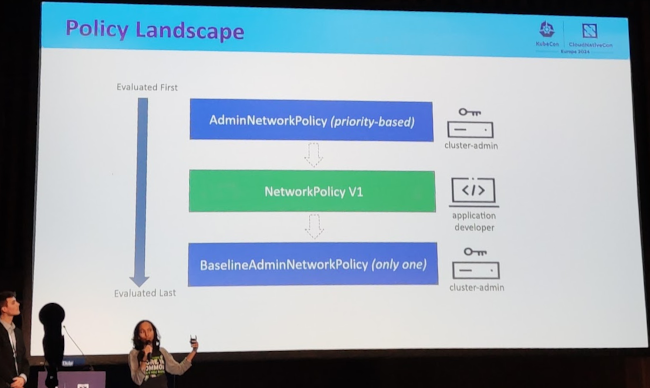

I very recently missed some semantics for limiting the number of open connections per namespace, see

I very recently missed some semantics for limiting the number of open connections per namespace, see

The twentyfirst release of

The twentyfirst release of  The Amazon Kids parental controls are extremely insufficient, and I strongly advise against getting any of the Amazon Kids series.

The initial permise (and some older reviews) look okay: you can set some time limits, and you can disable anything that requires buying.

With the hardware you get one year of the Amazon Kids+ subscription, which includes a lot of interesting content such as books and audio,

but also some apps. This seemed attractive: some learning apps, some decent games.

Sometimes there seems to be a special Amazon Kids+ edition , supposedly one that has advertisements reduced/removed and no purchasing.

However, there are so many things just wrong in Amazon Kids:

The Amazon Kids parental controls are extremely insufficient, and I strongly advise against getting any of the Amazon Kids series.

The initial permise (and some older reviews) look okay: you can set some time limits, and you can disable anything that requires buying.

With the hardware you get one year of the Amazon Kids+ subscription, which includes a lot of interesting content such as books and audio,

but also some apps. This seemed attractive: some learning apps, some decent games.

Sometimes there seems to be a special Amazon Kids+ edition , supposedly one that has advertisements reduced/removed and no purchasing.

However, there are so many things just wrong in Amazon Kids:

A welcome sign at Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi airport.

A welcome sign at Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi airport.

Bus from Suvarnabhumi Airport to Jomtien Beach in Pattaya.

Bus from Suvarnabhumi Airport to Jomtien Beach in Pattaya.

Road near Jomtien beach in Pattaya

Road near Jomtien beach in Pattaya

Photo of a songthaew in Pattaya. There are shared songthaews which run along Jomtien Second road and takes 10 bath to anywhere on the route.

Photo of a songthaew in Pattaya. There are shared songthaews which run along Jomtien Second road and takes 10 bath to anywhere on the route.

Jomtien Beach in Pattaya.

Jomtien Beach in Pattaya.

A welcome sign at Pattaya Floating market.

A welcome sign at Pattaya Floating market.

This Korean Vegetasty noodles pack was yummy and was available at many 7-Eleven stores.

This Korean Vegetasty noodles pack was yummy and was available at many 7-Eleven stores.

Wat Arun temple stamps your hand upon entry

Wat Arun temple stamps your hand upon entry

Wat Arun temple

Wat Arun temple

Khao San Road

Khao San Road

A food stall at Khao San Road

A food stall at Khao San Road

Chao Phraya Express Boat

Chao Phraya Express Boat

Banana with yellow flesh

Banana with yellow flesh

Fruits at a stall in Bangkok

Fruits at a stall in Bangkok

Trimmed pineapples from Thailand.

Trimmed pineapples from Thailand.

Corn in Bangkok.

Corn in Bangkok.

A board showing coffee menu at a 7-Eleven store along with rates in Pattaya.

A board showing coffee menu at a 7-Eleven store along with rates in Pattaya.

In this section of 7-Eleven, you can buy a premix coffee and mix it with hot water provided at the store to prepare.

In this section of 7-Eleven, you can buy a premix coffee and mix it with hot water provided at the store to prepare.

Red wine being served in Air India

Red wine being served in Air India