After a

very long porting journey,

Launchpad is finally running on Python 3 across

all of our systems.

I wanted to take a bit of time to reflect on why my emotional responses to

this port differ so much from those of some others who ve done large ports,

such as the

Mercurial

maintainers.

It s hard to deny that we ve had to burn a lot of time on this, which I m

sure has had an opportunity cost, and from one point of view it s

essentially running to stand still: there is no single compelling feature

that we get solely by porting to Python 3, although it s clearly a

prerequisite for tidying up old compatibility code and being able to use

modern language facilities in the future. And yet, on the whole, I found

this a rewarding project and enjoyed doing it.

Some of this may be because by inclination I m a maintenance programmer and

actually enjoy this sort of thing. My default view tends to be that

software version upgrades may be a pain but it s much better to get that

pain over with as soon as you can rather than trying to hold back the tide;

you can certainly get involved and try to shape where things end up, but

rightly or wrongly I can t think of many cases when a righteously indignant

user base managed to arrange for the old version to be maintained in

perpetuity so that they never had to deal with the new thing (

OK, maybe Perl

5 counts here).

I think a more compelling difference between Launchpad and Mercurial,

though, may be that very few other people really had a vested interest in

what Python version Launchpad happened to be running, because it s all

server-side code (aside from some client libraries such as

launchpadlib, which were ported

years ago). As such, we weren t trying to do this with the internet having

Strong Opinions at us. We were doing this because it was obviously the only

long-term-maintainable path forward, and in more recent times because some

of our library dependencies were starting to drop support for Python 2 and

so it was obviously going to become a practical problem for us sooner or

later; but if we d just stayed on Python 2 forever then fundamentally hardly

anyone else would really have cared directly, only maybe about some indirect

consequences of that. I don t follow Mercurial development so I may be

entirely off-base, but if other people were yelling at me about how late my

project was to finish its port, that

in itself would make me feel more

negatively about the project even if I thought it was a good idea. Having

most of the pressure come from ourselves rather than from outside meant that

wasn t an issue for us.

I m somewhat inclined to think of the process as an extreme version of

paying down technical debt. Moving from Python 2.7 to 3.5, as we just did,

means skipping over multiple language versions in one go, and if similar

changes had been made more gradually it would probably have felt a lot more

like the typical dependency update treadmill. I appreciate why not everyone

might want to think of it this way: maybe this is just my own rationalization.

Reflections on porting to Python 3

I m not going to defend the Python 3 migration process; it was pretty rough

in a lot of ways. Nor am I going to spend much effort relitigating it here,

as it s already been done to death elsewhere, and as I understand it the

core Python developers have got the message loud and clear by now. At a

bare minimum, a lot of valuable time was lost early in Python 3 s lifetime

hanging on to flag-day-type porting strategies that were impractical for

large projects, when it should have been providing for bilingual

strategies (code that runs in both Python 2 and 3 for a transitional period)

which is where most libraries and most large migrations ended up in

practice. For instance, the early advice to library maintainers to maintain

two parallel versions or perhaps translate dynamically with

2to3 was

entirely impractical in most non-trivial cases and wasn t what most people

ended up doing, and yet the idea that

2to3 is all you need still floats

around Stack Overflow and the like as a result. (These days, I would

probably point people towards something more like

Eevee s porting

FAQ

as somewhere to start.)

There are various fairly straightforward things that people often suggest

could have been done to smooth the path, and I largely agree: not removing

the

u'' string prefix only to put it back in 3.3, fewer gratuitous

compatibility breaks in the name of tidiness, and so on. But if I had a

time machine, the number one thing I would ask to have been done differently

would be introducing type annotations in Python 2 before Python 3 branched

off. It s true that it s

technically

possible

to do type annotations in Python 2, but the fact that it s a different

syntax that would have to be fixed later is offputting, and in practice it

wasn t widely used in Python 2 code. To make a significant difference to

the ease of porting, annotations would need to have been introduced early

enough that lots of Python 2 library code used them so that porting code

didn t have to be quite so much of an exercise of manually figuring out the

exact nature of string types from context.

Launchpad is a complex piece of software that interacts with multiple

domains: for example, it deals with a database,

HTTP, web page rendering,

Debian-format archive publishing, and multiple revision control systems, and

there s often overlap between domains. Each of these tends to imply

different kinds of string handling. Web page rendering is normally done

mainly in Unicode, converting to bytes as late as possible; revision control

systems normally want to spend most of their time working with bytes,

although the exact details vary;

HTTP is of course bytes on the wire, but

Python s

WSGI interface has some

string type

subtleties.

In practice I found myself thinking about at least four string-like types

(that is, things that in a language with a stricter type system I might well

want to define as distinct types and restrict conversion between them):

bytes, text, ordinary native strings (

str in either language, encoded to

UTF-8 in Python 2), and native strings with

WSGI s encoding rules. Some of

these are emergent properties of writing in the intersection of Python 2 and

3, which is effectively a specialized language of its own without coherent

official documentation whose users must intuit its behaviour by comparing

multiple sources of information, or by referring to unofficial porting

guides: not a very satisfactory situation. Fortunately much of the

complexity collapses once it becomes possible to write solely in Python 3.

Some of the difficulties we ran into are not ones that are typically thought

of as Python 2-to-3 porting issues, because they were changed later in

Python 3 s development process. For instance, the

email module was

substantially improved in around the 3.2/3.3 timeframe to handle Python 3 s

bytes/text model more correctly, and since Launchpad sends quite a few

different kinds of email messages and has some quite picky tests for exactly

what it emits, this entailed a lot of work in our email sending code and in

our test suite to account for that. (It took me a while to work out whether

we should be treating raw email messages as bytes or as text; bytes turned

out to work best.) 3.4 made some tweaks to the implementation of

quoted-printable encoding that broke a number of our tests in ways that took

some effort to fix, because the tests needed to work on both 2.7 and 3.5.

The list goes on. I got quite proficient at digging through Python s git

history to figure out when and why some particular bit of behaviour had changed.

One of the thorniest problems was parsing

HTTP form data. We mainly rely on

zope.publisher for this, which

in turn relied on

cgi.FieldStorage; but

cgi.FieldStorage is

badly broken in some

situations on Python 3. Even if that

bug were fixed in a more recent version of Python, we can t easily use

anything newer than 3.5 for the first stage of our port due to the version

of the base

OS we re currently running, so it wouldn t help much. In the

end I fixed some minor issues in the

multipart module (and was kindly

given co-maintenance of it) and

converted zope.publisher to use

it. Although

this took a while to sort out, it seems to have gone very well.

A couple of other interesting late-arriving issues were around

pickle. For most things

we normally prefer safer formats such as

JSON, but there are a few cases

where we use pickle, particularly for our session databases. One of my

colleagues pointed out that I needed to remember to tell

pickle to

stick

to protocol

2,

so that we d be able to switch back and forward between Python 2 and 3 for a

while; quite right, and we later ran into a similar problem with

marshal too. A more

surprising problem was that

datetime.datetime objects pickled on Python 2

require special care when unpickling

on Python 3; rather than the approach that ended up being implemented and

documented

for Python 3.6, though, I preferred a

custom

unpickler,

both so that things would work on Python 3.5 and so that I wouldn t have to

risk affecting the decoding of other pickled strings in the session database.

General lessons

Writing this over a year after Python 2 s end-of-life date, and certainly

nowhere near the leading edge of Python 3 porting work, it s perhaps more

useful to look at this in terms of the lessons it has for other large

technical debt projects.

I mentioned in my

previous article that

I used the approach of an enormous and frequently-rebased git branch as a

working area for the port, committing often and sometimes combining and

extracting commits for review once they seemed to be ready. A port of this

scale would have been entirely intractable without a tool of similar power

to

git rebase, so I m very glad that we finished migrating to git in 2019.

I relied on this right up to the end of the port, and it also allowed for

quick assessments of how much more there was to land.

git

worktree was also helpful, in that I

could easily maintain working trees built for each of Python 2 and 3 for comparison.

As is usual for most multi-developer projects, all changes to Launchpad need

to go through code review, although we sometimes make exceptions for very

simple and obvious changes that can be self-reviewed. Since I knew from the

outset that this was going to generate a lot of changes for review, I

therefore structured my work from the outset to try to make it as easy as

possible for my colleagues to review it. This generally involved keeping

most changes to a somewhat manageable size of 800 lines or less (although

this wasn t always possible), and arranging commits mainly according to the

kind of change they made rather than their location. For example, when I

needed to fix issues with

/ in Python 3 being true division rather than

floor division, I did so in

one

commit

across the various places where it mattered and took care not to mix it with

other unrelated changes. This is good practice for nearly any kind of

development, but it was especially important here since it allowed reviewers

to consider a clear explanation of what I was doing in the commit message

and then skim-read the rest of it much more quickly.

It was vital to keep the codebase in a working state at all times, and

deploy to production reasonably often: this way if something went wrong the

amount of code we had to debug to figure out what had happened was always

tractable. (Although I can t seem to find it now to link to it, I saw an

account a while back of a company that had taken a flag-day approach instead

with a large codebase. It seemed to work for them, but I m certain we

couldn t have made it work for Launchpad.)

I can t speak too highly of Launchpad s test suite, much of which originated

before my time. Without a great deal of extensive coverage of all sorts of

interesting edge cases at both the unit and functional level, and a

corresponding culture of maintaining that test suite well when making new

changes, it would have been impossible to be anything like as confident of

the port as we were.

As part of the porting work, we split out a couple of substantial chunks of

the Launchpad codebase that could easily be decoupled from the core: its

Mailman integration and its

code import

worker. Both of these had substantial

dependencies with complex requirements for porting to Python 3, and

arranging to be able to do these separately on their own schedule was

absolutely worth it. Like disentangling balls of wool, any opportunity you

can take to make things less tightly-coupled is probably going to make it

easier to disentangle the rest. (I can see a tractable way forward to

porting the code import worker, so we may well get that done soon. Our

Mailman integration will need to be rewritten, though, since it currently

depends on the Python-2-only Mailman 2, and Mailman 3 has a different architecture.)

Python lessons

Our

database layer was already in pretty good

shape for a port, since at least the modern bits of its table modelling

interface were already strict about using Unicode for text columns. If you

have any kind of pervasive low-level framework like this, then making it be

pedantic at you in advance of a Python 3 port will probably incur much less

swearing in the long run, as you won t be trying to deal with quite so many

bytes/text issues at the same time as everything else.

Early in our port, we established a standard set of

__future__ imports

and started incrementally converting files over to them, mainly because we

weren t yet sure what else to do and it seemed likely to be helpful.

absolute_import was definitely reasonable (and not often a problem in our

code), and

print_function was annoying but necessary. In hindsight I m

not sure about

unicode_literals, though. For files that only deal with

bytes and text it was reasonable enough, but as I mentioned above there were

also a number of cases where we needed literals of the language s native

str type, i.e. bytes in Python 2 and text in Python 3: this was

particularly noticeable in

WSGI contexts, but also cropped up in

some other

surprising

places. We

generally either omitted

unicode_literals or used

six.ensure_str in such

cases, but it was definitely a bit awkward and maybe I should have listened

more to people telling me it might be a bad idea.

A lot of Launchpad s early tests used

doctest, mainly in the

style

where you have text files that interleave narrative commentary with

examples. The development team later reached consensus that this was best

avoided in most cases, but by then there were far too many doctests to

conveniently rewrite in some other form. Porting doctests to Python 3 is

really annoying. You run into all the little changes in how objects are

represented as text (particularly

u'...' versus

'...', but plenty of

other cases as well); you have next to no tools to do anything useful like

skipping individual bits of a doctest that don t apply; using

__future__

imports requires the rather obscure approach of adding the relevant names to

the doctest s globals in the relevant

DocFileSuite or

DocTestSuite;

dealing with many exception tracebacks requires something like

zope.testing.renormalizing;

and whatever code refactoring tools you re using probably don t work

properly. Basically, don t have done that. It did all turn out to be

tractable for us in the end, and I managed to avoid using much in the way of

fragile doctest extensions aside from the aforementioned

zope.testing.renormalizing, but it was not an enjoyable experience.

Regressions

I know of nine regressions that reached Launchpad s production systems as a

result of this porting work; of course there were various other regressions

caught by

CI or in manual testing. (Considering the size of this project, I

count it as a resounding success that there were only nine production

issues, and that for the most part we were able to fix them quickly.)

Equality testing of removed database objects

One of the things we had to do while porting to Python 3 was to

implement

the

__eq__,

__ne__, and

__hash__ special methods for all our database

objects. This was quite conceptually fiddly, because doing this requires

knowing each object s primary key, and that may not yet be available if

we ve created an object in Python but not yet flushed the actual

INSERT

statement to the database (most of our primary keys are auto-incrementing

sequences). We thus had to take care to flush pending

SQL statements in

such cases in order to ensure that we know the primary keys.

However, it s possible to have a problem at the other end of the object

lifecycle: that is, a Python object might still be reachable in memory even

though the underlying row has been

DELETEd from the database. In most

cases we don t keep removed objects around for obvious reasons, but it can

happen in caching code, and buildd-manager

crashed as a result (in

fact while it was still running on Python 2). We had to

take extra

care

to avoid this problem.

Debian imports crashed on non-

UTF-8 filenames

Python 2 has some

unfortunate

behaviour around passing

bytes or Unicode strings (depending on the platform) to

shutil.rmtree, and

the combination of some

porting

work

and a particular source package in Debian that contained a non-

UTF-8 file

name caused us to run into this. The

fix

was to ensure that the argument passed to

shutil.rmtree is a

str

regardless of Python version.

We d actually run into

something

similar

before: it s a subtle porting gotcha, since it s quite easy to end up

passing Unicode strings to

shutil.rmtree if you re in the process of

porting your code to Python 3, and you might easily not notice if the file

names in your tests are all encoded using

UTF-8.

lazr.restful ETags

We eventually got far enough along that we could switch one of our four

appserver machines (we have quite a number of other machines too, but the

appservers handle web and

API requests) to Python 3 and see what happened.

By this point our extensive test suite had shaken out the vast majority of

the things that could go wrong, but there was always going to be room for

some interesting edge cases.

One of the Ubuntu kernel team reported that they were seeing an increase in

412 Precondition

Failed errors in some

of their scripts that use our webservice

API. These can happen when you re

trying to modify an existing resource: the underlying protocol involves

sending an

If-Match header with the

ETag that the client thinks the

resource has, and if this doesn t match the

ETag that the server calculates

for the resource then the client has to refresh its copy of the resource and

try again. We initially thought that this might be legitimate since it can

happen in normal operation if you collide with another client making changes

to the same resource, but it soon became clear that something stranger was

going on: we were getting inconsistent

ETags for the same object even when

it was unchanged. Since we d recently switched a quarter of our appservers

to Python 3, that was a natural suspect.

Our

lazr.restful package provides the framework for our webservice

API,

and roughly speaking it generates

ETags by serializing objects into some

kind of canonical form and hashing the result. Unfortunately the

serialization was dependent on the Python version in a few ways, and in

particular it serialized lists of strings such as lists of bug tags

differently: Python 2 used

[u'foo', u'bar', u'baz'] where Python 3 used

['foo', 'bar', 'baz']. In

lazr.restful 1.0.3 we

switched to using

JSON

for this, removing the Python version dependency and ensuring consistent

behaviour between appservers.

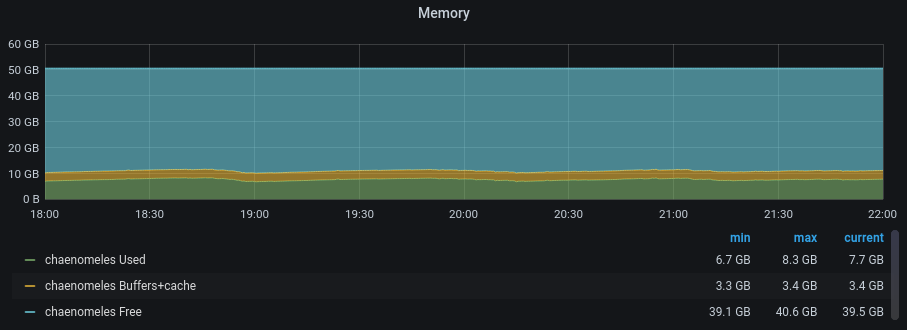

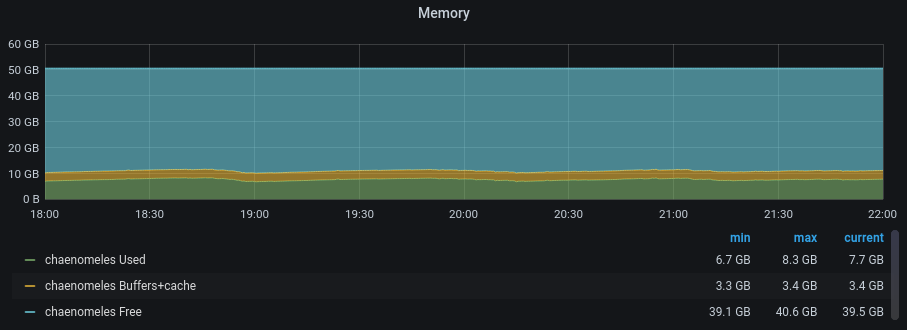

Memory leaks

This problem took the longest to solve. We noticed fairly quickly from our

graphs that the appserver machine we d switched to Python 3 had a serious

memory leak. Our appservers had always been a bit leaky, but now it wasn t

so much a small hole that we can bail occasionally as the boat is sinking rapidly :

(Yes, this got in the way of working out what was going on with

ETags for

a while.)

I spent ages messing around with various attempts to fix this. Since only

a quarter of our appservers were affected, and we could get by on 75%

capacity for a while, it wasn t urgent but it was definitely annoying.

After spending some quality time with

objgraph, for

some time I thought

traceback reference

cycles

might be at fault, and I sent a number of fixes to various upstream projects

for those (e.g.

zope.pagetemplate).

Those didn t help the leaks much though, and after a while it became clear

to me that this couldn t be the sole problem: Python has a cyclic garbage

collector that will eventually collect reference cycles as long as there are

no strong references to any objects in them, although it might not happen

very quickly. Something else must be going on.

Debugging reference leaks in any non-trivial and long-running Python program

is extremely arduous, especially with ORMs that naturally tend to end up

with lots of cycles and caches. After a while I formed a hypothesis that

zope.server might be keeping a

strong reference to something, although I never managed to nail it down more

firmly than that. This was an attractive theory as we were already in the

process of migrating to

Gunicorn for

other reasons anyway, and Gunicorn also has a convenient

max_requests

setting that s good at mitigating memory leaks. Getting this all in place

took some time, but once we did we found that everything was much more stable:

This isn t completely satisfying as we never quite got to the bottom of the

leak itself, and it s entirely possible that we ve only papered over it

using

max_requests: I expect we ll gradually back off on how frequently we

restart workers over time to try to track this down. However,

pragmatically, it s no longer an operational concern.

Mirror prober

HTTPS proxy handling

After we switched our script servers to Python 3, we had several reports of

mirror probing

failures. (Launchpad

keeps lists of Ubuntu archive and image mirrors, and probes them every so

often to check that they re reasonably complete and up to date.) This only

affected

HTTPS mirrors when probed via a proxy server, support for which is

a relatively recent feature in Launchpad and involved some code that we

never managed to unit-test properly: of course this is exactly the code that

went wrong. Sadly I wasn t able to sort out that gap, but at least the

fix

was simple.

Non-

MIME-encoded email headers

As I mentioned above, there were substantial changes in the

email package

between Python 2 and 3, and indeed between minor versions of Python 3. Our

test coverage here is pretty good, but it s an area where it s very easy to

have gaps. We noticed that a script that processes incoming email was

crashing on messages with headers that were non-

ASCII but not

MIME-encoded (and

indeed then crashing again when it tried to send a notification of the

crash!). The only examples of these I looked at were spam, but we still

didn t want to crash on them.

The

fix

involved being somewhat more careful about both the handling of headers

returned by Python s email parser and the building of outgoing email

notifications. This seems to be working well so far, although I wouldn t be

surprised to find the odd other incorrect detail in this sort of area.

Failure to handle non-

ISO-8859-1

URL-encoded form input

Remember how I said that parsing

HTTP form data was thorny? After we

finished upgrading all our appservers to Python 3, people started reporting

that they

couldn t post Unicode comments to

bugs, which turned out

to be only if the attempt was made using JavaScript, and was because I

hadn t quite managed to get

URL-encoded form data working properly with

zope.publisher and

multipart. The current standard describes the

URL-encoded format for form data as

in many ways an aberrant

monstrosity ,

so this was no great surprise.

Part of the problem was some

very strange

choices in

zope.publisher dating back to 2004 or earlier, which I attempted to

clean

up and simplify.

The rest was that Python 2 s

urlparse.parse_qs unconditionally decodes

percent-encoded sequences as

ISO-8859-1 if they re passed in as part of a

Unicode string, so

multipart needs to

work around

this on Python 2.

I m still not completely confident that this is correct in all situations,

but at least now that we re on Python 3 everywhere the matrix of cases we

need to care about is smaller.

Inconsistent marshalling of Loggerhead s disk cache

We use

Loggerhead for providing web

browsing of Bazaar branches. When we upgraded one of its two servers to

Python 3, we immediately noticed that the one still on Python 2 was failing

to read back its revision information cache, which it stores in a database

on disk. (We noticed this because it caused a deployment to fail: when we

tried to roll out new code to the instance still on Python 2, Nagios checks

had already caused an incompatible cache to be written for one branch from

the Python 3 instance.)

This turned out to be a similar problem to the

pickle issue mentioned

above, except this one was with

marshal, which I didn t think to look for

because it s a relatively obscure module mostly used for internal purposes

by Python itself; I m not sure that Loggerhead should really be using it in

the first place. The fix was

relatively

straightforward,

complicated mainly by now needing to cope with throwing away unreadable

cache data.

Ironically, if we d just gone ahead and taken the nominally riskier path of

upgrading both servers at the same time, we might never have had a problem here.

Intermittent bzr failures

Finally, after we upgraded one of our two Bazaar codehosting servers to

Python 3, we had a

report of intermittent

bzr branch hangs. After some digging I found this in our logs:

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

File "/srv/bazaar.launchpad.net/production/codehosting1-rev-20124175fa98fcb4b43973265a1561174418f4bd/env/lib/python3.5/site-packages/twisted/conch/ssh/channel.py", line 136, in addWindowBytes

self.startWriting()

File "/srv/bazaar.launchpad.net/production/codehosting1-rev-20124175fa98fcb4b43973265a1561174418f4bd/env/lib/python3.5/site-packages/lazr/sshserver/session.py", line 88, in startWriting

resumeProducing()

File "/srv/bazaar.launchpad.net/production/codehosting1-rev-20124175fa98fcb4b43973265a1561174418f4bd/env/lib/python3.5/site-packages/twisted/internet/process.py", line 894, in resumeProducing

for p in self.pipes.itervalues():

builtins.AttributeError: 'dict' object has no attribute 'itervalues'

I d seen this before in our git hosting service: it was a bug in Twisted s

Python 3 port,

fixed after

20.3.0 but unfortunately after the last release that supported Python 2, so

we had to backport that patch. Using the same backport dealt with this.

Onwards!

The following contributors got their Debian Developer accounts in the last two months:

The following contributors got their Debian Developer accounts in the last two months:

There is a bit of context that needs to be shared before I get to this and would be a long one. For reasons known and unknown, I have a lot of sudden electricity outages. Not just me, all those who are on my line. A discussion with a lineman revealed that around 200+ families and businesses are on the same line and when for whatever reason the electricity goes for all. Even some of the traffic lights don t work. This affects software more than hardware or in some cases, both. And more specifically HDD s are vulnerable. I had bought an APC unit several years for precisely this, but over period of time it just couldn t function and trips also when the electricity goes out. It s been 6-7 years so can t even ask customer service to fix the issue and from whatever discussions I have had with APC personnel, the only meaningful difference is to buy a new unit but even then not sure this is an issue that can be resolved, even with that.

That comes to the issue that happens once in a while where the system fsck is unable to repair /home and you need to use an external pen drive for the same. This is my how my hdd stacks up

There is a bit of context that needs to be shared before I get to this and would be a long one. For reasons known and unknown, I have a lot of sudden electricity outages. Not just me, all those who are on my line. A discussion with a lineman revealed that around 200+ families and businesses are on the same line and when for whatever reason the electricity goes for all. Even some of the traffic lights don t work. This affects software more than hardware or in some cases, both. And more specifically HDD s are vulnerable. I had bought an APC unit several years for precisely this, but over period of time it just couldn t function and trips also when the electricity goes out. It s been 6-7 years so can t even ask customer service to fix the issue and from whatever discussions I have had with APC personnel, the only meaningful difference is to buy a new unit but even then not sure this is an issue that can be resolved, even with that.

That comes to the issue that happens once in a while where the system fsck is unable to repair /home and you need to use an external pen drive for the same. This is my how my hdd stacks up  The main argument as have shared before is that Indian Govt. thinks we need our home grown CPU and while I have no issues with that, as shared before except for RISC-V there is no other space where India could look into doing that. Especially after the Chip Act, Biden has made that any new fabs or any new thing in chip fabrication will only be shared with

The main argument as have shared before is that Indian Govt. thinks we need our home grown CPU and while I have no issues with that, as shared before except for RISC-V there is no other space where India could look into doing that. Especially after the Chip Act, Biden has made that any new fabs or any new thing in chip fabrication will only be shared with

. Backups certainly make a lot of sense, especially

. Backups certainly make a lot of sense, especially  Welcome to the 40th post in the

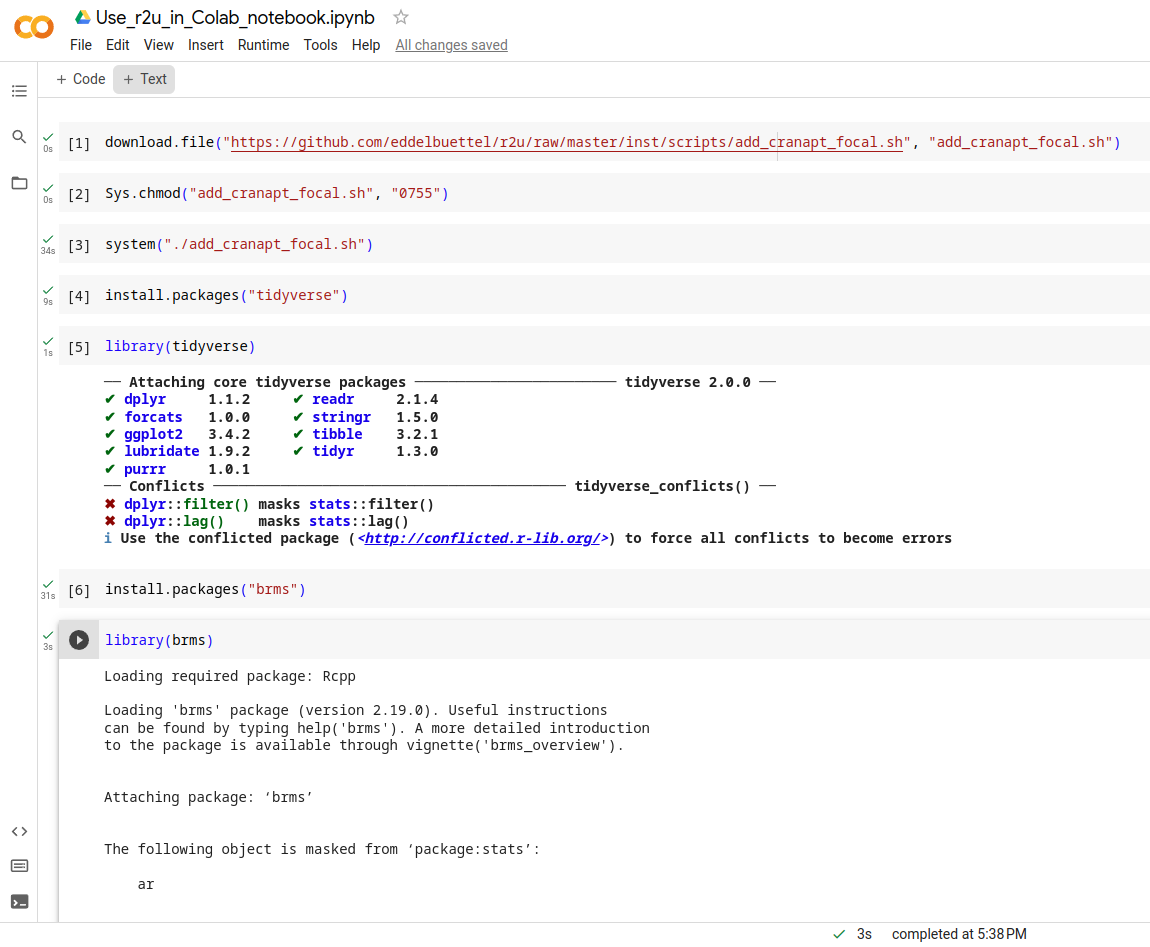

Welcome to the 40th post in the  r2u on colab focal

r2u on colab focal

This post marks the beginning my yearly roundups of the favourite books and movies that I read and watched in 2022 that I plan to publish over the next few days.

Just as I did for

This post marks the beginning my yearly roundups of the favourite books and movies that I read and watched in 2022 that I plan to publish over the next few days.

Just as I did for

Uhm yeah, so this shirt didn t age well. :) Mainly to recall what happened, I m once again revisiting my previous year (previous edition:

Uhm yeah, so this shirt didn t age well. :) Mainly to recall what happened, I m once again revisiting my previous year (previous edition:

After a

After a  (Yes, this got in the way of working out what was going on with

(Yes, this got in the way of working out what was going on with  This isn t completely satisfying as we never quite got to the bottom of the

leak itself, and it s entirely possible that we ve only papered over it

using

This isn t completely satisfying as we never quite got to the bottom of the

leak itself, and it s entirely possible that we ve only papered over it

using