Review:

The Unbroken, by C.L. Clark

| Series: |

Magic of the Lost #1 |

| Publisher: |

Orbit |

| Copyright: |

March 2021 |

| ISBN: |

0-316-54267-9 |

| Format: |

Kindle |

| Pages: |

490 |

The Unbroken is the first book of a projected fantasy trilogy. It

is C.L. Clark's first novel.

Lieutenant Touraine is one of the Sands, the derogatory name for the

Balladairan Colonial Brigade. She, like the others of her squad, are

conscript soldiers, kidnapped by the Balladairan Empire from their

colonies as children and beaten into "civilized" behavior by Balladairan

training. They fought in the Balladairan war against the Taargens. Now,

they've been reassigned to El-Wast, capital city of Qaz l, the foremost of

the southern colonies. The place where Touraine was born, from which she

was taken at the age of five.

Balladaire is not France and Qaz l is not Algeria, but the parallels are

obvious and strongly implied by the map and the climates.

Touraine and her squad are part of the forces accompanying Princess Luca,

the crown princess of the Balladairan Empire, who has been sent to take

charge of Qaz l and quell a rebellion. Luca's parents died in the

Withering, the latest round of a recurrent plague that haunts Balladaire.

She is the rightful heir, but her uncle rules as regent and is reluctant

to give her the throne. Qaz l is where she is to prove herself. If she

can bring the colony in line, she can prove that she's ready to rule: her

birthright and her destiny.

The Qaz li are uninterested in being part of Luca's grand plan of personal

accomplishment. She steps off her ship into an assassination attempt,

foiled by Touraine's sharp eyes and quick reactions, which brings the Sand

to the princess's attention. Touraine's reward is to be assigned the

execution of the captured rebels, one of whom recognizes her and names her

mother before he dies. This sets up the core of the plot: Qaz li

rebellion against an oppressive colonial empire, Luca's attempt to use the

colony as a political stepping stone, and Touraine caught in between.

One of the reasons why I am happy to see increased diversity in SFF

authors is that the way we tell stories is shaped by our cultural

upbringing. I was taught to tell stories about colonialism and rebellion

in a specific ideological shape. It's hard to describe briefly, but the

core idea is that being under the rule of someone else is unnatural as

well as being an injustice. It's a deviation from the way the world

should work, something unexpected that is inherently unstable. Once

people unite to overthrow their oppressors, eventual success is

inevitable; it's not only right or moral, it's the natural path of

history. This is what you get when you try to peel the supremacy part

away from white supremacy but leave the unshakable self-confidence and

bedrock assumption that the universe cares what we think.

We were also taught that rebellion is primarily ideological. One may be

motivated by personal injustice, but the correct use of that injustice is

to subsume it into concepts such as freedom and democracy. Those concepts

are more "real" in some foundational sense, more central to the right

functioning of the world, than individual circumstance. When the

now-dominant group tells stories of long-ago revolution, there is no

personal experience of oppression and survival in which to ground the

story; instead, it's linked to anticipatory fear in the reader, to the

idea that one's privileges could be taken away by a foreign oppressor and

that the counter to this threat is ideological unity.

Obviously, not every white fantasy author uses this story shape, but the

tendency runs deep because we're taught it young. You can see it

everywhere in fantasy, from

Lord of the Rings to

Tigana.

The Unbroken uses a much

different story shape, and I don't think it's a coincidence that the

author is Black.

Touraine is not sympathetic to the Qaz li. These are not her people and

this is not her life. She went through hell in Balladairan schools, but

she won a place, however tenuous. Her personal role model is General

Cantic, the Balladairan Blood General who was also one of her instructors.

Cantic is hard as nails, unforgiving, unbending, and probably a war

criminal, but also the embodiment of a military ethic. She is tough but

fair with the conscript soldiers. She doesn't put a stop to their

harassment by the regular Balladairan troops, but neither does she let it

go too far. Cantic has power, she knows how to keep it, and there is a

place for Touraine in Cantic's world.

And, critically, that place is not just hers: it's one she shares with her

squad. Touraine's primary loyalty is not to Balladaire or to Qaz l. It's

to the Sands. Her soldiers are neither one thing nor the other, and they

disagree vehemently among themselves about what Qaz l and their other

colonial homes should be to them, but they learned together, fought

together, and died together. That theme is woven throughout

The

Unbroken: personal bonds, third and fourth loyalties, and practical

ethics of survival that complicate and contradict simple dichotomies of

oppressor and oppressed.

Touraine is repeatedly offered ideological motives that the protagonist in

the typical story shape would adopt. And she repeatedly rejects them for

personal bonds: trying to keep her people safe, in a world that is not

looking out for them.

The consequence is that this book tears Touraine apart. She tries to walk

a precarious path between Luca, the Qaz li, Cantic, and the Sands, and she

falls off that path a lot. Each time I thought I knew where this book was

going, there's another reversal, often brutal. I tend to be a

happily-ever-after reader who wants the protagonist to get everything they

need, so this isn't my normal fare. The amount of hell that Touraine goes

through made for difficult reading, worse because much of it is due to her

own mistakes or betrayals. But Clark makes those decisions believable

given the impossible position Touraine is in and the lack of role models

she has for making other choices. She's set up to fail, and the price of

small victories is to have no one understand the decisions that she makes,

or to believe her motives.

Luca is the other viewpoint character of the book (and yes, this is also a

love affair, which complicates both of their loyalties). She is the

heroine of a more typical genre fantasy novel: the outsider princess with

a physical disability and a razor-sharp mind, ambitious but fair (at least

in her own mind), with a trusted bodyguard advisor who also knew her

father and a sincere desire to be kinder and more even-handed in her

governance of the colony. All of this is real; Luca is a protagonist, and

the reader is not being set up to dislike her. But compared to Touraine's

grappling with identity, loyalty, and ethics, Luca is never in any real

danger, and her concerns start to feel too calculated and superficial.

It's hard to be seriously invested in whether Luca proves herself or gets

her throne when people are being slaughtered and abused.

This, I think, is the best part of this book. Clark tells a traditional

ideological fantasy of learning to be a good ruler, but she puts it

alongside a much deeper and more complex story of multi-faceted

oppression. She has the two protagonists fall in love with each other and

challenges them to understand each other, and Luca does not come off well

in this comparison. Touraine is frustrated, impulsive, physical, and

sometimes has catastrophically poor judgment. Luca is analytical and

calculating, and in most ways understands the political dynamics far

better than Touraine. We know how this story usually goes: Luca sees

Touraine's brilliance and lifts her out of the ranks into a role of

importance and influence, which Touraine should reward with loyalty. But

Touraine's world is more real, more grounded, and more authentic, and both

Touraine and the reader know what Luca could offer is contingent and comes

with a higher price than Luca understands.

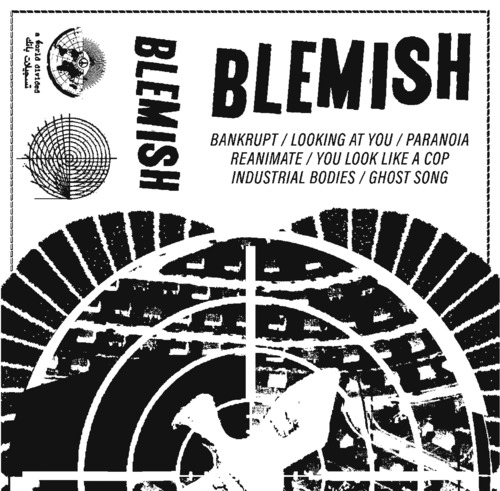

(Incidentally, the cover of

The Unbroken, designed by Lauren

Panepinto with art by Tommy Arnold, is astonishingly good at capturing

both Touraine's character and the overall feeling of the book. Here's a

larger version.)

The writing is good but uneven. Clark loves reversals, and they did keep

me reading, but I think there were too many of them. By the end of the

book, the escalation of betrayals and setbacks was more exhausting than

exciting, and I'd stopped trusting anything good would last. (Admittedly,

this is an accurate reflection of how Touraine felt.) Touraine's inner

monologue also gets a bit repetitive when she's thrashing in the jaws of

an emotional trap. I think some of this is first-novel problems of

over-explaining emotional states and character reasoning, but these

problems combine to make the book feel a bit over-long.

I'm also not in love with the ending. It's perhaps the one place in the

book where I am more cynical about the politics than Clark is, although

she does lay the groundwork for it.

But this book is also full of places small and large where it goes a

different direction than most fantasy and is better for it. I think my

favorite small moment is Touraine's quiet refusal to defend herself

against certain insinuations. This is such a beautiful bit of

characterization; she knows she won't be believed anyway, and refuses to

demean herself by trying.

I'm not sure I can recommend this book unconditionally, since I think you

have to be in the mood for it, but it's one of the most thoughtful and

nuanced looks at colonialism and rebellion I can remember seeing in

fantasy. I found it frustrating in places, but I'm also still thinking

about it. If you're looking for a political fantasy with teeth, you could

do a lot worse, although expect to come out the other side a bit battered

and bruised.

Followed by

The Faithless, and I have no idea where Clark is going

to go with the second book. I suppose I'll have to read and find out.

Content note: In addition to a lot of violence, gore, and death, including

significant character death, there's also a major plague. If you're not

feeling up to reading about panic caused by contageous illness, proceed

with caution.

Rating: 7 out of 10

20 years ago, I got my Debian Developer account. I was 18 at the time, it was Shrove Tuesday and - as is customary - I was drunk when I got the email. There was so much that I did not know - which is also why the process took 1.5 years from the time I applied. I mostly only maintained a package or two. I'm still amazed that Christian Perrier and Joerg Jaspert put sufficient trust in me at that time. Nevertheless now feels like a good time for a personal reflection of my involvement in Debian.

20 years ago, I got my Debian Developer account. I was 18 at the time, it was Shrove Tuesday and - as is customary - I was drunk when I got the email. There was so much that I did not know - which is also why the process took 1.5 years from the time I applied. I mostly only maintained a package or two. I'm still amazed that Christian Perrier and Joerg Jaspert put sufficient trust in me at that time. Nevertheless now feels like a good time for a personal reflection of my involvement in Debian.

Most of my Debian contributions this month were

Most of my Debian contributions this month were

On the riscv64 port, the default boot method is UEFI, with

On the riscv64 port, the default boot method is UEFI, with

I've been pondering what should happen to personal websites once the owner has

passed, or otherwise "moved on". Some time ago I stumbled across a

I've been pondering what should happen to personal websites once the owner has

passed, or otherwise "moved on". Some time ago I stumbled across a