Ian Jackson: UPS, the Useless Parcel Service; VAT and fees

I recently had the most astonishingly bad experience with UPS, the courier company. They severely damaged my parcels, and were very bad about UK import VAT, ultimately ending up harassing me on autopilot.

The only thing that got their attention was my draft Particulars of Claim for intended legal action.

Surprisingly, I got them to admit in writing that the disbursement fee they charge recipients alongside the actual VAT, is just something they made up with no legal basis.

What happened

Autumn last year I ordered some furniture from a company in Germany. This was to be shipped by them to me by courier. The supplier chose UPS.

UPS misrouted one of the three parcels to Denmark. When everything arrived, it had been sat on by elephants. The supplier had to replace most of it, with considerable inconvenience and delay to me, and of course a loss to the supplier.

But this post isn t mostly about that. This post is about VAT. You see, import VAT was due, because of fucking Brexit.

UPS made a complete hash of collecting that VAT. Their computers can t issue coherent documents, their email helpdesk is completely useless, and their automated debt collection systems run along uninfluenced by any external input.

The crazy, including legal threats and escalating late payment fees, continued even after I paid the VAT discrepancy (which I did despite them not yet having provided any coherent calculation for it).

This kind of behaviour is a very small and mild version of the kind of things British Gas did to Lisa Ferguson, who eventually won substantial damages for harassment, plus 10K of costs.

Having tried asking nicely, and sending stiff letters, I too threatened litigation.

I would have actually started a court claim, but it would have included a claim under the Protection from Harassment Act. Those have to be filed under the Part 8 procedure , which involves sending all of the written evidence you re going to use along with the claim form. Collating all that would be a good deal of work, especially since UPS and ControlAccount didn t engage with me at all, so I had no idea which things they might actually dispute. So I decided that before issuing proceedings, I d send them a copy of my draft Particulars of Claim, along with an offer to settle if they would pay me a modest sum and stop being evil robots at me.

Rather than me typing the whole tale in again, you can read the full gory details in the PDF of my draft Particulars of Claim. (I ve redacted the reference numbers).

Outcome

The draft Particulars finally got their attention. UPS sent me an offer: they agreed to pay me 50, in full and final settlement. That was close enough to my offer that I accepted it. I mostly wanted them to stop, and they do seem to have done so. And I ve received the 50.

VAT calculation

They also finally included an actual explanation of the VAT calculation. It s absurd, but it s not UPS s absurd:

comments

comments

The clearance was entered initially with estimated import charges of 400.03, consisting of 387.83 VAT, and 12.20 disbursement fee. This original entry regrettably did not include the freight cost for calculating the VAT, and as such when submitted for final entry the VAT value was adjusted to include this and an amended invoice was issued for an additional 39.84. HMRC calculate the amount against which VAT is raised using the value of goods, insurance and freight, however they also may apply a VAT adjustment figure. The VAT Adjustment is based on many factors (Incidental costs in regards to a shipment), which includes charge for currency conversion if the invoice does not list values in Sterling, but the main is due to the inland freight from airport of destination to the final delivery point, as this charge varies, for example, from EMA to Edinburgh would be 150, from EMA to Derby would be 1, so each year UPS must supply HMRC with all values incurred for entry build up and they give an average which UPS have to use on the entry build up as the VAT Adjustment. The correct calculation for the import charges is therefore as follows: Goods value divided by exchange rate 2,489.53 EUR / 1.1683 = 2,130.89 GBP Duty: Goods value plus freight (%) 2,130.89 GBP + 5% = 2,237.43 GBP. That total times the duty rate. X 0 % = 0 GBP VAT: Goods value plus freight (100%) 2,130.89 GBP + 0 = 2,130.89 GBP That total plus duty and VAT adjustment 2,130.89 GBP + 0 GBP + 7.49 GBP = 2,348.08 GBP. That total times 20% VAT = 427.67 GBP As detailed above we must confirm that the final VAT charges applied to the shipment were correct, and that no refund of this is therefore due.This looks very like HMRC-originated nonsense. If only they had put it on the original bills! It s completely ridiculous that it took four months and near-litigation to obtain it. Disbursement fee One more thing. UPS billed me a 12 disbursement fee . When you import something, there s often tax to pay. The courier company pays that to the government, and the consignee pays it to the courier. Usually the courier demands it before final delivery, since otherwise they end up having to chase it as a debt. It is common for parcel companies to add a random fee of their own. As I note in my Particulars, there isn t any legal basis for this. In my own offer of settlement I proposed that UPS should:

State under what principle of English law (such as, what enactment or principle of Common Law), you levy the disbursement fee (or refund it).To my surprise they actually responded to this in their own settlement letter. (They didn t, for example, mention the harassment at all.) They said (emphasis mine):

A disbursement fee is a fee for amounts paid or processed on behalf of a client. It is an established category of charge used by legal firms, amongst other companies, for billing of various ancillary costs which may be incurred in completion of service. Disbursement fees are not covered by a specific law, nor are they legally prohibited. Regarding UPS disbursement fee this is an administrative charge levied for the use of UPS deferment account to prepay import charges for clearance through CDS. This charge would therefore be billed to the party that is responsible for the import charges, normally the consignee or receiver of the shipment in question. The disbursement fee as applied is legitimate, and as you have stated is a commonly used and recognised charge throughout the courier industry, and I can confirm that this was charged correctly in this instance.On UPS s analysis, they can just make up whatever fee they like. That is clearly not right (and I don t even need to refer to consumer protection law, which would also make it obviously unlawful). And, that everyone does it doesn t make it lawful. There are so many things that are ubiquitous but unlawful, especially nowadays when much of the legal system - especially consumer protection regulators - has been underfunded to beyond the point of collapse. Next time this comes up I might have a go at getting the fee back. (Obviously I ll have to pay it first, to get my parcel.) ParcelForce and Royal Mail I think this analysis doesn t apply to ParcelForce and (probably) Royal Mail. I looked into this in 2009, and I found that Parcelforce had been given the ability to write their own private laws: Schemes made under section 89 of the Postal Services Act 2000. This is obviously ridiculous but I think it was the law in 2009. I doubt the intervening governments have fixed it. Furniture Oh, yes, the actual furniture. The replacements arrived intact and are great :-).

Welcome to the 39th post in the relatively randomly recurring rants,

or

Welcome to the 39th post in the relatively randomly recurring rants,

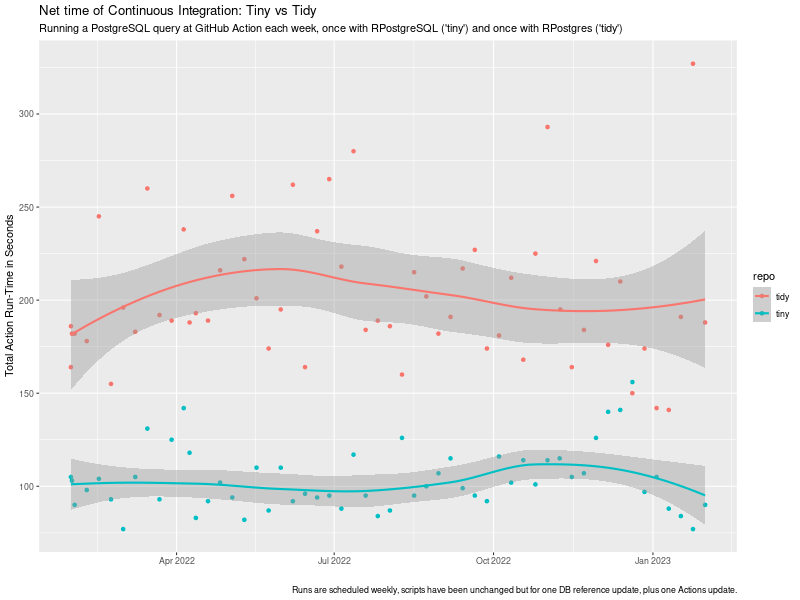

or  tiny vs tidy ci timing impact

chart

tiny vs tidy ci timing impact

chart